by William Irwin Thompson

A book made the founding of the Lindisfarne Association possible, so the story of Lindisfarne is entwined with the story of this curious little book that did not follow the usual path to publication, nor the usual road to post-publication success.

The book was At the Edge of History and was published by Harper & Row in 1971. It arrived at the editorial offices in the mail, without the representation of an agent, because I was naïve enough not to know that the chances of a book being accepted through the mail were 1 in 7,500.

For unexplainable reasons, the young editorial assistant, Christie Noyes, whose task it was to deal with the towering dead weight of all those manuscripts dumped on her desk turned the pages quickly and asked the manuscript to give her a signal to put it in the rejections list, but she kept getting little signs that asked her to grant it a stay of execution.

Like Sheherazade postponing her fate with another interconnected story, the manuscript caught her interest. The stay of execution turned into a full pardon and the manuscript was carried to the senior editor’s desk, Buz Wyeth, and from there to acceptance and the contracts department.

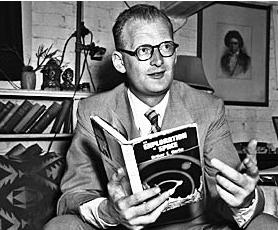

While the manuscript was moving from galleys to page proofs, Arthur C. Clarke appeared in the editorial offices on one of his visits from Sri Lanka. Since my concluding chapter had a riff on his book and the movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey, he was shown the pages and was delighted. As Clarke moved about Manhattan, from Harper & Row to The New Yorker, he shared his enthusiasm and talked about the book everywhere, giving it a murmuring buzz around the book even before it was published.

Arthur C. Clarke

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, the reviewer for The New York Times, decided to review At the Edge of History, which, considering the hundreds of books he had to choose from, was no small act of intercessionary grace in itself. He gave the book a rave review, but as rave reviews were not uncommon, what truly astonished everyone in Manhattan was that three days later in the middle of reviewing another book, he stopped mid-column and admitted that he could not get At the Edge of History out of his mind, and had been haunted by it.

Harper & Row was delighted and took out an ad in The New York Times that proclaimed: “so extraordinary–The New York Times raved twice!” Now everyone in Manhattan was talking about the book. It became a bestseller, but only in Manhattan, which was good enough to make the top ten list in Time magazine for the week. Since many of the people talking about the book in the city were executives, these would one day be the very people I would see in order to incorporate Lindisfarne as a not for profit corporation, and from whom I would seek foundation grants.

Away from the talk of Manhattan, up in suburban Toronto, I began to receive phone calls to appear on David Frost and the Dick Cavett Show. To the horror of Harper & Row, I declined both and tried to explain to them that I was not a television celebrity but a writer, one more interested in creating a lifetime’s oeuvre than becoming a celebrity or a narcississtic habitué of talk shows.

As I focused in my mind on my high school heroes of Whitehead, Yeats, and Thomas Mann, I held to an image of culture that had disappeared with them. I simply did not understand that there was no longer any such thing as a successful writer who was not a TV celebrity – with the single exception of Thomas Pynchon. With more than 32,000 books published a year then, it was impossible for a book to survive simply on its literary merits. Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer, and Susan Sontag understood this only too well, but I did not.

On the basis of the book, the editor of The New York Times, Harrison Salisbury, asked me to do several OpEd page essays, and as these too stirred up talk around town – one was even read aloud by an actor before a play on Off-Broadway. The book continued to sell well in Manhattan, but nowhere else in the country, so the sales began to dwindle.

Fortunately for me, while the book was still hot, I was able to get a good advance for my next book, Passages about Earth, and these funds enabled me to finance a trip around the world, one that ended with my visit to the ruined abbey of Lindisfarne on Holy Island in Northumbria.

The book took another upward turn in its life, when it was short-listed for the National Book Award in early 1972. And when the award went to the Whole Earth Catalogue, one of the judges quit in protest to giving a literary award to a hippie Yellow Pages catalogue. The next day the American historian Max Lerner protested in his column in the New York Daily News and said that the award should have gone to At the Edge of History.

Although Frank Sinatra had hymned “New York, New York! If you can make it there, you can make it anywhere,” those sentiments proved to be truer of the forties than the seventies. The book became a bestseller only for a season in Manhattan and nowhere else. In Chicago, Dallas, and L.A., people watched TV to find out what people were talking about, and since I wasn’t on TV, I was under the edge of their history.

While the book received good reviews in Manhattan and the Los Angeles Times, it was not universally well received, and more conservative reviewers in more solidly academic journals, such as the Virginia Quarterly and the Partisan Review,dismissed the work as apocalyptic and more a symptom of the decline of Western Civilization than a description of its end. These august and Augustan defenders of the dominant Neo-Roman imperial culture were suspicious of wild, mystical, and otherworldly Celts, and my particular re-visioning of history – and their elitist position at its center – was simply unacceptable. They were, of course, right about me; I was apocalyptic, but I had good reason to be, and in my writings I strove to be reasonable about why I did not place much faith in reality.

One good reason for becoming paranoid is to grow up in an environment in which the news never tells the real truth while your peripheral senses pick up on an invisible environment of menace. I grew up in the age when America itself was paranoid and broadcast news of the global threat of communism. In my parochial elementary school, the nuns taught us how, at the sound of the single command “Drop!” to leap under our desks to seek the protection of a one inch thick slab of wood from a Hydrogen bomb.

The government, however, offered us no protection from American atom bombs and continued their open air atomic explosions in Nevada; and when the Santa Ana desert winds would blow the contaminated dust into the air and onto the grazing lands around the city, no one said that the contaminated milk should be destroyed rather than given to the children whose thyroid glands absorbed the Iodine 131. At ten, I would rise at dawn to witness the marvel of the eastern sky lighting up from atomic bombs in man’s preemptive strike at dawn; at eleven, I had cancer of the thyroid.

If I was sick, the environment was also sick. The air was brown with smog. Everyone smoked everywhere. The shoe stores were filled with Xray machines in which I could play as a child and look at my bones in an eerie green light. At my Catholic parochial school we were warned to be suspicious of cultured intellectuals who were more likely to be communist sympathizers, and on the new medium of television we were taught by our Hollywood producers to dislike unruly Arabs and revere Israelis.

This was not hard, as the Israeli dessert frontier seemed to be another sort of Western with a Cowboys and Indians conflict. (Small wonder that Sharon tried to break up the West Bank into reservations.) I can still remember the United Jewish Appeal’s image on TV and in newsreels of Ben Gurion on a hill in Israel, with a new wind lifting his white hair in the Promised Land.

David Ben-Gurion

When you can’t really know what is truly going on around you, you begin to grow up with a sense of unease and dread. I looked to books to deliver me from the media, so I had a vague distrust of television. I wanted to grow up to become a writer and not a television star or politician. But I was not strong enough in my youth to be completely immune to the new political medium. I could see at once how repulsive Senator Joe McCarthy was, but like most of my generation I was taken in by the media manipulations of the Kennedys and when I came of age and exercised my first vote, it was for the appealing JFK over the dour and droning five o’clock-shadowed delusionary Richard Milhous Nixon.

But what had been a nebulous atmosphere of unexpressed menace in the nineteen-fifties became a clear and distinct threat in the sixties in the days of the Cuban Missile Crisis—which we now know was indeed a time when we hung by our fingernails above the abyss of thermonuclear war.

In 1962, I was a first year graduate student at Cornell. My friends from Pomona College, Leon Leeds and Linda Thompson, were with me as we examined our apartment and realized that the only place we could escape the imploding glass of the windows was in the closet under the stairs. Leon, then a graduate student from Indiana, was visiting his girl friend Linda–later to become his wife–who was also a graduate student with me in the English department at Cornell. As we listened to the news, we talked about places where one could live, far away from the cities, in some imaginary communal “return to nature.”

The Cuban missile crisis came and went, but there was no let-up on the environment of hidden menace and public lies as JFK and Martin Luther King were assassinated, and the country shifted from its fifties postwar culture of consumerism to race riots in Detroit, Newark, and Watts, and radical left bombings and open talk of revolution. A new youth culture appeared, whose avatars were Bob Dylan and the Beatles, and no one believed what the political leaders were saying anymore, not simply about the War in Viet Nam and the global communist menace, but about the nature of reality itself. Reality was broken and needed fixing.

In those unstable times, studying literature and following the deconstructionist leadership of Paul De Man at Cornell seemed too nihilistic and valueless. Of course, at that time I did not know that De Man had written fascist and anti-Semitic articles for Belgium newspapers in the early forties; I was simply repelled at his way of reading Yeats and the whole aura around him when he lectured.

I turned away from the approaches of all my professors of English and Comparative Literature at Cornell to return to my own anthropological approach of my Pomona College days and began to study another time of insurrection in Ireland. I didn’t want to decenter authorial narratives in the post-modernist thinking of Paul De Man and Roland Barthes, I wanted to study the role of the artist as a prophetic figure who rearticulated the relationship between myth and history. I wanted to understand the role of the imagination in the transformation of culture. The revolutionary Ireland of nationalist Patrick Pearse on the one side, and mystical conservative William Butler Yeats on the other, seemed the perfect place to pursue a new line of cultural inquiry.

Although I never knew my maternal grandmother, Margaret Mary O’Leary–since she had died when my mother was a child–I had listened to my mother in Chicago talk about her Irish mother and grandmother, so these invisible beings became mythical ancestors for me. My colleagues in my graduate seminar on James Joyce were drawn to study Ulysses or Finnegans Wake as if they were verbal crossword puzzles to be solved, but I was drawn to the historical horizon behind Joyce. I shifted away from studying to become a literary critic to becoming a cultural historian and chose to write my dissertation on the insurrection in Dublin in 1916, the Easter Rising, the nationalist movement that started the process of the dismemberment of the British Empire. As I was finishing my dissertation, and getting ready to take my first teaching job in the Department of Humanities at MIT, Los Angeles went up in flames in the insurrection in Watts of 1965.

In the winter of 1966-1967, I received an MIT Old Dominion faculty fellowship that allowed me to take off a semester from teaching to do research. I thought of going back to Dublin and London, but I felt this strong pull back to California. From L.A. to San Francisco and Berkeley it seemed as if history was happening out there, so studying history in the libraries of Dublin and London seemed too antiquarian for my years, as I was still in my twenties.

I flew to L.A., and then in the summer of ’67 drove up to Esalen in Big Sur, where I met Alan Watts, Joan Baez, and Esalen’s founder, Michael Murphy. There are times in history when to be at the right place at the right age is to feel a state of exaltation. Wordsworth felt it in France in the early days of the Revolution, before the Terror: Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive/But to be young was very Heaven![i]

Joan Baez and Judy Collins at the Esalen Institute Folk Festival, 1967

Michael Murphy and Dick Price – Co-Founders of the Esalen Institute; Big Sur, CA

I didn’t take acid, because as a child of four I had experienced what I later realized was yogic samadhi while listening to classical music, and, as an adolescent of eighteen, I had experienced Daimonic transmissions, the spontaneous elevation of kundalini, and the opening of the third eye while listening to Beethoven’s Ninth string quartet. In one of these transmissions, I was warned against taking the path of drugs; however, at that moment in Esalen–unlike President Clinton–I did inhale when Alan Watts passed me his joint as we soaked in the tubs, and I passed it on to the gloriously beautiful naked woman on my right.

Alan Watts in the ’60s

I was able to resist losing myself in sex, drugs, and rock and roll at Esalen, but what really took possession of me during my conversations at the wine bar with Michael Murphy was the idea of the countercultural institution—of completely breaking away from academe and creating a completely different sort of institution. I didn’t cheat on my wife, but held on tightly to my weakening grasp of monogamy, but I did cheat on MIT and the muse I became embedded with was not Erato but Clio as I used my research fellowship to shift away from purely academic research to begin writing what became At the Edge of History.

The more I worked on the book, the harder it became to endure MIT, especially during the Viet Nam War when the faculty was polarized between the Defense Industry Hawks and the Marxist Doves under the aggressive bird of prey leadership of Noam Chomsky and Louis Kampf.

Earth Sciences Building and Calder Stabile, MIT

Under Louis Kampf’s direction, the Literature Division took a radical Left turn and he hired several Maoist-inspired radicals who argued in faculty meetings that we should stop teaching works like Wordsworth’s Prelude, because the self was a bourgeois-personalist fiction, and that we should teach Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice instead.

Since I was interested in the evolution of consciousness, and the coeval emergence of phenomenological models for the growth and development of the mind in Hegel, Wordsworth, and Coleridge, this forceful eliminativism of the Leftist radicals took away the literary and philosophical classics and cultural history I was interested in exploring. In the spirit of Foucault, the humanities at MIT became focused exclusively on power, technology, and the means of production. The third way that Esalen was exploring, and that I would continue to develop through Lindisfarne in the Seventies and Eighties became impossible at MIT.

On one side, MIT was an instrument for the enforced modernization of traditional cultures in Viet Nam and the traditional Humanities; and on the other, it was a suburban revolutionary cabal lost in fantasies about Mao–whom we now know was responsible for the deaths of more people than either Hitler or Stalin. Like the I. M. Pei building for the Earth Sciences that stood on pylons to bestride the world like a colossus, both the Right and Left sides of MIT took the earth for granted, and ecology there was all about the domination of nature.

I quit MIT and went off to Toronto, and certainly Toronto in the age of Marshall McLuhan and Canada in the age of Trudeau was a good place to be, but my brand new suburban drive-in university was not Esalen. Leon Leeds, now an archaeologist, joined me to teach in the Humanities Division of York University, and in the spirit of the times we went back to our discussions of rural communal life, and he and his wife Linda joined my family on a rented fifteen acre farm in Bradford, Ontario and from there we commuted to campus, which was at the northernmost edge of suburban Toronto.

I kept at work on my book, and when invited to the 1969 Lake Couchiching conference in Ontario, I shared the first draft of my chapter on MIT with the audience. At that conference was Ivan Illich. He was the most charismatic speaker I had ever encountered, and when he spoke of the need for creating “counterfoil institutions,” I knew that it was not simply MIT I had to leave, but the institution of the university itself. Michael Murphy’s Esalen in Big Sur and Ivan Illich’s CIDOC in Cuernavaca began to appear as morning stars on the horizon at the dawn of the seventies…

Ivan Illich

To read Part 2, click here.

MOST VIEWED

- The Three Spinners: A Syrian Folktale20 views

- Song Lyrics as Literature18 views

- Marjane Satrapi on the Graphic Novel, Family History, and Adventures in Cinema10 views

- La Tunda, Child of the Devil and Other Traditional Afro-Ecuadorian Stories9 views

- The Childhood Memories Series by Jacqueline Bishop6 views

- Open Borders6 views

- Diary of a Writer in Midlife Crisis5 views

- On the Road to Tarascon: Francis Bacon Meets Vincent Van Gogh5 views

- Eric Steginsky5 views

- Mystical Dimensions of Islam4 views

William Irwin Thompson

William Irwin Thompson (born July, 1938) is known primarily as a social philosopher and cultural critic, but he has also been writing and publishing poetry throughout his career and received the Oslo International Poetry Festival Award in 1986. He has made significant contributions to cultural history, social criticism, the philosophy of science, and the study of myth. He describes his writing and speaking style as “mind-jazz on ancient texts”. He is an astute reader of science, social science, history, and literature. He is the founder of the Lindisfarne Association.

His book, Still Travels: Three Long Poems was published in 2009 by Wild River Books. Order a copy from Amazon.

WEBSITE: www.williamirwinthompson.org

Works by William Irwin Thompson

Book Reviews

Locus Amoenus by Victoria Alexander

Thinking Otherwise – On Turkey: Anatolian Days and Nights

Lindisfarne Cafe

Memoir – Farewell Address at the Lindisfarne Fellows Conference

Memoir – Pilgrimage to Lindisfarne: 1972

Memoir – The Founding of the Lindisfarne Association in New York, 1971-73 – Part I

Memoir – The Founding of the Lindisfarne Association in New York, 1971-73 – Part 2: A Community in Fishcove, Long Island

Memoir – Building a Dream – Part One: Lindisfarne in Crestone, Colorado, 1979-1997

Memoir – My Dinner with Andre Gregory: Lindisfarne-in-Manhattan, 1977-1979

Memoir – Building a Dream/The Shadow Side Part Two: Lindisfarne in Crestone, Colorado, 1979-1997

Memoir – Building a Dream/The Cathedral Part Three: Lindisfarne in Crestone, Colorado, 1979-1997

Memoir – Conclusion: The Economic Relevance of Lindisfarne

Memoir – Raising Evan and Hilary: Reflections of a Homeschooling Parent

Memoir – Sex and the Commune

Memoir – Raising Evan and Hilary

Memoir – With Gregory Bateson’s Mind in Nature

Poetry

After Heart Surgery: Hokusai’s Great Wave

Canticum, Turicum

Its Time

A Lazy Sunday Afternoon

Manhattan Morning

Nancy Grayson’s Bookstore

On Reading “The Penguin Book of English Verse”: on my iPad and Exercise Bike

Vade-Mecum Angelon

Wild River Books/Poetry – Nightwatch and Dayshift: Cezanne

Winter Haiku

Thinking Otherwise

Anatolian Days and Nights and the Cultural Evolution of Spirituality

And the Votes are In: The American Elections of 2010

Avatar – When Technology Displaces Culture

Bedtime Story for a Civilization

The Big Picture: Reflections on Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines

The Big Picture, II

Child Abuse and the Catholic Church

The Digital Economy of W. Brian Arthur

From Shamanism to Religion, Part Two

From Religion to Post-Religious Spirituality, Part Three

From Religion to Post-Religious Spirituality: Conclusion

January 1, 2011: Reflections on the Philosophical Notions of Republicans

January 6, 2011 – Part Two: The Etherealization of Capitalism

Nature and Invisible Environments

Of Culture and the Nature of Extinction

On Nuclear Power

On Religion – Part One

On Religion and Nationalism: Ireland, Israel, and Palestine

On Transnational Military Interventions

A Pagan Ur-Text of the Lebor Gebála Érenn

Part 1 – The Shift from Industrial to a Planetary Civilization

Part 2 – The Shift from an Industrial to Planetary Civilization

Part 3 – The Shift from an Industrial to a Planetary Civilization – The Recovery of a Cosmic Orientation

Part 4 – The Shift from an Industrial to a Planetary Civlization – The Global War for Drugs

Part 5 – The Shift from an Industrial to a Planetary Civilization – The New Jerusalem

Part 6 – The Shift from an Industrial to a Planetary Civilization – Catastrophes as the Spur to Institute Tricameral Legislature

Part 7 – The Shift from an Industrial to a Planetary Civilization – Complex Dynamical Systems and Tricameral Legislatures

Part 8 – The Shift from a Industrial to a Planetary Civilization – Israel and Palestine: Sic transit gloria mundi

Part 9 – The Shift from an Industrial to a Planetary Civlization – On Sarah Palin and the Technocratic Society

Part 10 – The Shift from an Industrial to a Planetary Civilization – On Conspiracy Narratives as Expressive of the Transition from the Nation: State to the Noetic Polity

Part 11 – The Shift from an Industrial to a Planetary Civilization – Global Awareness and Personal Identity

Part 12 – The Shift from an Industrial to a Planetary Civilization – Conclusion: The United Nations

Political Meditation for the Fourth of July, 2011: Can We Shift from Empire Back to Republic?

St. David’s Day, 2011, Technology and Social Change

Saint Patrick’s Day, 2010: Us and Them: Identity and the State

Some Reflections on Hurricane Sandy and an Outline for a New Civilization

Technical Hubris: and the Sinkhole of Obama’s Centrism

Television and Social Class

Thanksgiving Day, 2010: The Uses and Abuses of History

The Elections of 2010

Thoughts on My new Kindle App: on My Mac iPad

Contact Info

Wild River Review

P.O. Box 53

Stockton, New Jersey 08559

U.S.A.

info@wildriverreview.com